Sum: Word Maps, composed by Gil McElroy during the early 80’s, and published by Cameron Anstee’s Apt. 9 Press in 2017 is a quiet book of visual/written information. As the title suggests, the pieces are a series of maps, each map a word regarded in its placement among the alphabet set out in a simple grid, a-z, displayed in two lines. It was, according to McElroy, a dissatisfaction with a lot of visual poetry he had encountered in and around the 70’s and early 80’s which “struck [him] as trite, especially by comparison with what visual artists … were doing with language”.

Sum: Word Maps, composed by Gil McElroy during the early 80’s, and published by Cameron Anstee’s Apt. 9 Press in 2017 is a quiet book of visual/written information. As the title suggests, the pieces are a series of maps, each map a word regarded in its placement among the alphabet set out in a simple grid, a-z, displayed in two lines. It was, according to McElroy, a dissatisfaction with a lot of visual poetry he had encountered in and around the 70’s and early 80’s which “struck [him] as trite, especially by comparison with what visual artists … were doing with language”.

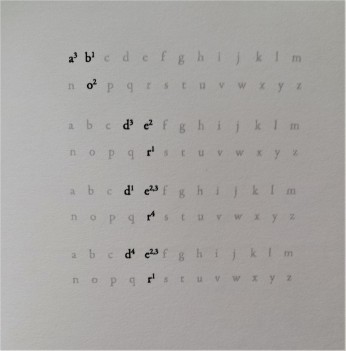

When I picked up Word Maps from Anstee’s table at the Small Press Book Fair in Toronto at the end of last year (2017), the soft noise of the light grey alphabet grids which appear on each page, the black of the letters scattered throughout the grids drew me in. Without having any inkling what was happening within the pages of the book, the only slightly varied (at first glance) visual information was already being processed, my imagination filling in (reflex) what might be occurring on the pages.

Cameron and I spoke about the book and he mentioned that unlike the enthusiasm which I immediately showed, another not long before had made the comment that the work, the presentation, was a gimmick. I get the feeling that people say gimmick when work finds unfamiliar form, and when perhaps, the poem doesn’t perform an expected routine.

What is a gimmick? The Merriam Webster Dictionary defines it as,

1 a : a mechanical device for secretly and dishonestly controlling gambling apparatus

b : an ingenious or novel mechanical device : gadget

2 a : an important feature that is not immediately apparent : catch

b : an ingenious and usually new scheme or angle

c : a trick or device used to attract business or attention

Without beating around the bush, I’m going to make the assumption that gimmick was used in the last sense, a trick or device used to attract business or attention. So, what’s the gimmick? And what is the unsubstantial centre that makes a gimmick necessary? If the trick or device used to attract attention is the grid form, then stripped of that one would be faced with words, floating on the page, chosen for no apparent reason, which we would read as some poetic constellation of juxtaposed images/notions. But that would entirely defeat the purpose of Word Maps, which seeks to “see words – the purely visual unit – differently, to strip away anything hinting of meaning, connotation, metaphor … and consider the pure artifact”. It seems to be a gimmick only if you think visual poetry’s a farce.

Not that the work entirely succeeds either—at least where the author intended. The more cursory the glance, the more the work achieves the purely visual unit. But, I find that the work does succeed when the reader doesn’t assist in the effort to evade meaning. The initial encounter with these poems is one of facing scaffolding. If the reader decides to stop there, so be it—but the natural impulse, it seems to me, is to investigate which words are in fact being used. How can one resist deciphering once the journey into the work has begun? And once the words begin to come together, isn’t the natural next impulse to wonder just why those words were chosen? Read and one finds palindromes (kayak), words which use the same letters so that they mirror each other on the grid, despite their difference (angle/angel), and further linguistic choices which create visual patterns.

If the grid is a map, it is also a playground, and only by actively entering these arenas of play and engaging the rules of the game can the purely visual unit be appreciated, when, the moment the reader takes a step back, all recognition of the words and their meanings again collapse into the scaffolding. The reader can struggle the words into order, but paradoxically, the rigid grid bounces them back into noise.

All quotations taken from McElroy’s afterword, After Words, in Sum: Word Maps.